Historical and Philosophical Tour

Our first journey within the 12 Tours to Navigate Digital Geneva takes us through the rich intellectual and philosophical heritage of Geneva, and covers topics that are relevant for addressing the key dilemmas of the digital age, as well as the challenges artificial intelligence (AI) has put before us. We will look back at history in order to see forward into the future.

Technology has been developing for centuries, from the invention of writing 3,000 years ago up to the latest AI technology. Despite the social differences in these periods, the challenges humanity faced, and is still facing, remain similar:

- What are the potentials and limits of rationality and progress?

- How will the technological choices we make today impact the future?

- What should the social contract between technology and humanity look like?

As we dive deep into Geneva’s tradition of thought, we invite you to suggest thinkers we might have missed, and include how you feel they are relevant for the digital age.

Our ‘Historical and Philosophical Tour’ starts in the narrow streets of Geneva’s Old Town where Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in 1712, and moves onto places and spaces where other Geneva thinkers have contributed to the development of human thought.

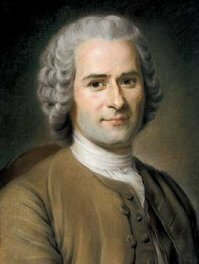

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, born in Geneva on 28 June 1712, was one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment. His most influential works were the Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract.

His political views are best summarised in the first line of The Social Contract: ‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.’ For Rousseau, therefore, it is up to individuals to accept this role of the state through a social contract.

Rousseau and the digital age

We follow with an excerpt from Jovan Kurbalija’s text What would Rousseau advise internet leaders today? written in 2012 on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of Rousseau’s birth.

Rousseau would not be particularly enthusiastic about either the old internet contract (run by the tech elite), nor the alternative proposals (the government-driven approach). For Rousseau, the core of a social contract is the process in which citizens (in this case internet citizens) actively participate in public debates and decision-making. This includes much more than occasional voting.

Rousseau would definitely argue for the establishment of the general will of all internet users around a few key principles (parallel to the current discussion of internet principles). He would be concerned about the number of social contractors (two billion internet users). He envisaged a social contract for small societies, modelled around his hometown of Geneva. Rousseau’s social contract is demanding for citizens. It requires a very active participation in political life, as well as continuing education towards achieving ‘civic skills’ (capacity building).

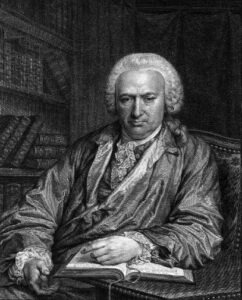

Charles Bonnet

Charles Bonnet was born in the thriving intellectual epicentre of Geneva in 1720. Being a botanist, lawyer, philosopher, psychologist, and politician were just a few parts of his rich academic pursuits.

Bonnet was a genuine Renaissance figure. He trained in law as a profession and enjoyed a brief political career, gaining membership to the Council of the Republic of Geneva from 1752 to 1768.

His initial scientific interests included insects and germs, but when he moved into botany, Bonnet made important observations by patiently studying the gas bubbles which formed on leaves that were submerged in water, indicating the existence of gas exchange (Recherches sur l’usage des feuilles dans les plantes).

Bonnet and the digital age

In his text Nature and digital: A historical view from Geneva from 2020, written on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of Bonnet’s birth, Jovan Kurbalija writes of the two legacies of Bonnet’s work which resonate over time.

First is his need to move beyond the siloed fields when discussing politics or conducting scientific research. Bonnet was, as reflected in his diverse opus, a ‘boundary spanner’; a type of thinker who we need today when society is diving deeper and deeper into siloed specialisations.

Second is his work on linking mathematics and nature, which today would inspire the work on regulating AI. Namely, one of the inputs in this debate could be the patterns that nature developed over time through ‘biological algorithms’. For example, Bonnet’s ‘mathematics’ in the distribution of leaves (the golden ratio) might inspire a search for a formula in dealing with AI and other digital challenges we are facing.

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley started writing Frankenstein on 16 June 1816 in Villa Diodati in Geneva. Together with Lord Byron and a group of friends, Shelley came to Geneva in search of better weather and some fun. While Geneva typically has more sunny days than London, this was not the case in 1816. That year, both cities missed summer weather, which was triggered by the eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies (the former Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia). In an article entitled What if Byron and the Shelleys had live tweeted from the Villa Diodati the author imagines a fictional exchange between the two writers on Twitter.

Shelley and the digital age

We follow with excerpts from Jovan Kurbalija’s text 200-year-old Frankenstein memory: Alive and well written in 2016 on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the night Shelly came up with the idea for Frankenstein.

Shelley was a big fan of science and experimentation. In the 19th century, science and technology were starting their unstoppable historical march, a march that continues today. (Un)intentionally, Shelley opened core questions on progress and ethics.

Today, science has advanced far beyond Luigi Galvani’s experiment with electricity and frog legs which inspired Shelley. Today, her protagonist Victor Frankenstein would have had a much easier job creating his creature. But, apart from technology, dilemmas from 1816 remain the same: How far can technology go in affecting core human features? Are there ethical limits for technological developments?

Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure was a Geneva-born linguist. His main contribution was built around three courses on linguistics that he delivered from 1906 to 1911 at the University of Geneva. After his premature death, his students organised Saussure’s lecture notes and published them in the book Course in General Linguistics in 1916. Translated into many languages, this book became the cornerstone of modern linguistics.

It is interesting that Saussure was a historical linguist. By studying the history of mainly Indo-European languages, he came to insights that shaped the future of linguistics, as well as the subsequent developments in the field of AI and machine learning.

Saussure and the digital age

Saussure’s work on language and systems laid the basis for natural language processing (NLP) and modern AI. The bridge between Saussure and the latest AI developments is represented in Alan Turing’s paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence (1950).

Saussure’s pioneering linguistic research on identifying language patterns and functions is conceptually the basis of modern NLP systems which are used for a wide range of AI-driven applications, from Google’s search and voice recognition to text generation.

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges lived the last years of his life in Geneva, just around the corner from the house where Rousseau was born. In his huge and diverse opus, Borges was the master of paradox and of addressing irreconcilable contradictions of human existence. Typically, his writings do not offer definite answers to human dilemmas. Instead, he takes readers on a journey showing that every certainty triggers a new uncertainty. He provides us with a humbling reflection of the human condition and the limits of our rationality.

Borges and the digital age

Borges’s fiction is inspirational reading for answering core questions of humanity’s future centred around the interplay between science, technology, and philosophy. His short story ‘The Library of Babel’, written in 1941, is a prophetic reading as it outlines the search for meaning in endless volumes of information as we do today on the internet. Borges’s thinking can inspire new solutions in dealing with fake news, competing narratives, and ultimately, the search for truth.

In addressing informational chaos, Borges shies away from giving a naive hope of certainty, but he does provide some hope by arguing for order in chaos, as well as that by taking an occasional rest, we can regain meaning, and stop, or at least slow down, the constantly shifting kaleidoscope of meaning.

Send your suggestions!

Have we missed anyone?

We invite you to send your suggestions of Geneva thinkers, philosophers, scientists, and writers whose insights could help us in addressing the crucial dilemmas of our digital future, such as:

- technology and ethics

- tech progress and societal harmony

- advancing human creativity

- striking various trade-offs between humanity and sci-tech developments

By completing the firm below you will contribute to the first of our tours: the one focusing on History and Philosophy in Geneva. At the end of all our 12 tours, the Geneva Internet Platform will copile its research and your contributions into a final publication which will help us navigate digital Geneva by theme.

You are most welcomed to circulate this form also among your colleagues.

For any questions, please contact Mr Marco Lotti at marcol@diplomacy.edu.